Obāchan Ie no Nioi (the smell of my grandma's house) Dt

text, fotos, variable dimension, 2022

![]()

There isn't a time line. It's not a linear equation. You start in the middle and unfold outward from there. It's not a flat surface that you walk back and forth on. It's like being inside a ball that isn't exactly a ball, but is really made up of thousands and thousands of small panels. And on each panel, there is a mirror, but each mirror reflects something different. And from where you crouch, if you turn your head up or around or down or sideways, you can see something new, something old, or something you've forgotten.

Forgetting or remembering something that never happened. Wondering when does one thing end and another begin? And if you can separate the two.

Two women take up two different roads, two different journeys at different times. They are not travelling with a specific destination in mind but the women are walking toward the same place. Whether they meet or not is not relevant.

This is not a mathematical equation.

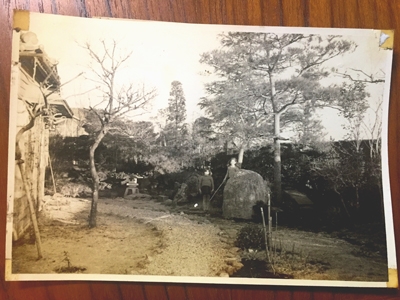

The memory of the dark one-story house on what was then a large lot where my mother grew up. I don’t remember what the house looks like. I see blurred dark brown and something dark green. I don't recognise anything else, even if I squint. Right next door, my Japanese aunt's family has built a bright, white, modern family home where we stay when we visit. Although in a suburb of Tokyo, the property and the surrounding area are quite green. These tall trees have long since given way to asphalt parking lots and apartment buildings now. There is a lot of money to be made from parking lots. Every square inch brings profit in this city.

I remember the typhoon breaking in abruptly between the tall chestnut trees, chestnuts with particularly long burrs pelt to the ground around me. Spines like toothpicks. Chestnuts, as I have never seen them before, hit the ground to the left and right of me. I am still quite small and flee with my hands wrapped protectively above my head. From somewhere a similar memory emerges of fist-sized hailstones in the English Garden in Munich, when a storm surprises us after a visit to the beer garden near the Chinese Tower. I'm about the same age. Balls of ice and chestnuts raining from the sky.

My grandmother's house. Dark, the smell of old, almost musty, damp, dark, cellar, mold. Despite being separated from the blistering hot glaring summer day by only a thin wall of wood, it is pleasantly dark in here. Almost cool, especially in contrast to the humid heat outside. Distinct to the modern, bright house, gleaming white in the sun where we, the relatives from Germany are staying, my grandmother's house is dark and old. It smells dark and old. The floor is built on stilts in the traditional way. Wooden floorboards, a few centimetres, maybe 30, above the ground. And above that a simple green carpet, old-fashioned dark green off-the-roll carpeting, the kind you can buy in hardware stores and garden centres. A rough plastic carpet that would be just as good for outside as in. I remember parts of the floor where, under the carpet, a board was missing. Rotten over the years and broken. The carpet runs over it, stretching over the hole. It’s only when you walk on it, and it gives way a little — your foot barely held by the carpet stretched over the empty space — that you realise you’re stepping into a hole.

Above it still the smell of old, damp and resinous wood, which I will forever associate with Japan.

I am sure my grandparents' old house was not standing for long after this memory was created. And my grandfather was also not alive for long either. After that, my grandmother lived in the new house until her death. There she lay in bed for many years, in a small bright room on the first floor. After her death, she was laid out in that room, on ice and flowers, and the family spent the night with her, drinking, eating nibbles and laughing, so that obāchan's soul would not be afraid and would feel encouraged to embark on the next journey.

At the time of this memory, however, grandmother and grandfather still live in the old, dark and, even in the humid summer heat, surprisingly cool wooden house with the green carpet stretching over the holes of the old floor, making sure that no one disappears into them. The house is surrounded by tall trees, from whose crowns chestnuts pelt down during the typhoon, striking down those who fail to protect themselves.

Old age made grandfather crazy. That said, they say he’s always been crazy. As a young man, he signed on with a merchant ship to avoid being drafted into the war. He found grandmother in Hiroshima working as a mathematics teacher. Such a profession, indeed any profession, at that time was uncommon for women in Japan. Together they fled from grandmother’s family, which was not willing to tolerate, let alone recognise, the dishonourable foreign marriage, and settled at the foot of Fuji-san. Yokatta, yokatta, otherwise the atomic bomb, which fell on the sixth of August, would have taken grandmother too. The bomb fell directly on the school where she taught mathematics. A profession so unusual for a young woman in Japan at that time.

A few years later my grandparents moved to the property on the outskirts of Tokyo and lived there, shunned by the neighbours because of their foreigner marriage and love, but which they held on to as it had saved their lives once before. The property had been large and green in the beginning, on the edge of fields from which my mother stole corncobs and melons and still fondly remembers adventures of this kind. In my Bavarian childhood, as soon as we drove past a cornfield my father would stop the car to give my mother and myself the opportunity to steal corncobs and awaken my mother’s fond memories of the large plot of land with the huge garden, which over the years has been halved over and over again, to make way for asphalt parking lots and more houses. The plot on which the modern, bright, family house was built, which for a few years stood next to the old house where my grandmother lived when my grandfather, who had always been a bit crazy, was still alive. Inside the house, green plastic carpet stretched across holes in the floor. It was damp, dark, almost cool, even in the greatest summer heat, with no air-conditioning. During a typhoon, chestnuts with spines like toothpicks would hail down outside. Those who did not know how to protect themselves were struck down and injured.

In my grandmother's house, where the resinous, fine smell of wood permeated everything, there were wondrous objects made of wood and paper. I sit on the green carpet. I have just been told not to deliberately step on the holes in the floor spanned by the carpet, although I particularly enjoy it. I’ve been sitting on the carpet for some time, breathing the cool, dark air. I’m handed old objects made of wood and paper. The sticky moisture I brought in from outside dries cool on my skin. I can't remember. Did I get the things as a gift? Should I play with them? Did I take them myself out of sheer curiosity? From outside through the windowpanes individual dusty sunbeams hesitantly hit the dark green carpet, leaving emerald-green stains. Tiny grains of dust float weightlessly in the silence.

Grandfather left a lot behind when, as a young man, he travelled to Japan as a missionary on a ship to avoid going to war, and soon fell in love with grandmother in Japan. Their foreign marriage caused them grief and their children suffered too. But if love had not, by chance, found them there, that maths teacher would not have left her family but continued to teach at that school. And it was precisely on that school that the bomb was dropped on the sixth of August, killing all its students. But not grandmother, who had so dishonourably left her parents and town with grandfather.

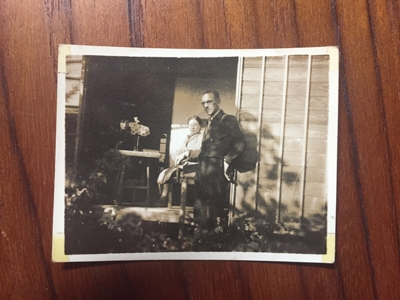

Grandfather had always been crazy. A tall, sharp-edged man from South Tyrol with an insatiable desire for Menhirs, large standing stones, some of which he’d had shipped from South Tyrol to his Japanese property’s garden. With the death of grandfather, the Menhirs disappeared from the garden. His son-in-law buried them. They had long been a thorn in his side. Had they been too rough in this foreign environment? Hidden in the Japanese earth they slumber now and think of my grandfather, of the high chestnuts where now only asphalted parking lots are for rent.

I hardly got to know my grandfather. That summer he chased me with his dentures, which he’d removed from his mouth and snapped at me in his big hand. I think that was his sense of humour, our game, in that humid summer among the tall trees where chestnuts still hung, even after the typhoon, and the heat burned.

In my grandmother's house, on the carpet, surrounded by the smell of old wood, I think I can't remember anything else. I breathe the cool air as I’m handed old objects made of wood and paper. Dusty sunbeams leave emerald-green stains, tiny dust grains float weightlessly in space. I hold a delicate box in my hands, and gently unfold it...

![]()